In the present section you can find information on the procedure for the production of Traditional Balsamic Vinegar generally. As regards the Balsamico of Modena we are unable to furnish a recipe, as it would be necessary first to have details which are available only to specialists; also, the companies producing this vinegar maintain the strictest secret of the procedure they adopt, as they consider it with great pride an ancestral patrimony that carries their own distinctive touch.

Procedure

1. The Traditional Balsamic of Modena is produced from local white grapes strictly defined by set rules; the most important grape is Trebbiano, which can be used also at the exclusion of others. Admitted are also all the red Lambrusco grapes, as well as the other red grapes traditionally cultivated together with the Lambrusco varieties proper.

2. Through the squashing of such grapes a must unadulterated by any chemical substances is obtained, and is simmered in open vases of capacities that vary in accordance with production needs.

3. A serious reduction and concentration results. The liquid is left to cool and to decant before being poured into the head barrels of the batteries.

4. Batteries are in fact series of casks of varying capacities, called vaselli, made of woods obtained from the several autochthonous essences: oak, false acacia, mulberry, acacia, chesnut and juniper -although the last of them, yielding through its resin a strong flavour to the Balsamico, is not always adopted in the regular series, but it is rather added apart. The casks getting proportionally smaller, they satisfy the treble function of acetification, maturation and ageing.

5. Treble having to be the function, the minimum number of the vaselli in a battery must be three, whilst theoretically there is no upper limit to their number, even though five seems to be the optimum. The most popular capacities vary from 50 litres for the largest cask, down to 10 litres for the smallest.

6. The largest vat receives the year’s simmered must; from the smallest is spilt the Balsamico ready for use; the unfinished product is added in the intermediate casks. As the contents of the smallest cask diminishes because of spilling, it is replaced for the correct quantity by taking from the cask immediately preceding, and this one in turn will have to be fed from the next preceding one, until the first and largest is reached. This, as said above, is replenished with the must obtained from the year’s harvest.

7. The denomination of Balsamico is limited to vinegars which, obtained in accordance with the procedure outlined above, have been started no less than 12 years before in a battery previously implanted with vinegar bacteria taken from other batteries already in full production.

8. Balsamico casks must not be filled completely, but only for two thirds of their capacity, as good airing is needed for the reaction.

9. Annual drawings of Balsamico so obtained must be quite parsimonious, as otherwise the remaining mix might be weakened and partly lose its characteristics. It is advisable not to draw more than 50% of the cask’s contents.

Making your own balsamic vinegar is not easy. The same chain of handing down the unwritten rules and customs related to the management of one’s family vinegar according to the rhythms of a peasant civilization, has rapidly diminished after millenary existence at the end of the last post-war period. The recovery in the last 25/30 years of a whole series of customs, including that of making balsamic vinegar, has allowed us to safeguard its future prospect and indeed has fueled an ever-growing interest in it.

Much has been written and many courses have been set up to train amateurs able to keep this tradition alive and the results are very flattering, but not always and not everyone is able to intervene in their own vinegar cellar with the due expertise and therefore not to ruin an inestimable patrimony it is necessary that they can turn to expert and competent personnel who can give the necessary advice and possibly lend their work directly where the vinegar factory would be subject to neglect or poor maintenance.

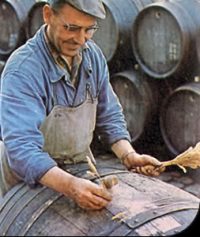

the types of wood used in the barrels

The choice of the suitable wood with which to build your own vinegar cellar is a fundamental element in the personalization of the same as well as an opportunity to decide a priori which character will have the product we are going to create. The centuries-old practice has meant that not all woods suitable for the construction of containers are equally suitable for containing and favoring the processes related to balsamic vinegar. Important woods such as walnut are excluded from the category of usable ones, while others apparently more humble rise in value for the balsamic cooper. The observation and experimentation by numerous generations of these precious craftsmen, once widespread due to the extensive use of wooden containers, has allowed us to identify with certainty the strengths and weaknesses, if any, of the tree species with the which balsamic barrels are built.

Chesnut

Sweet, workable and yet with good leak-proof qualities, thanks to its tannin is capable of giving the vinegar an intense dark colour. White after processing, in time it acquires more typical shades. With a quite complex and not always regular vein, it remains among the most appreciated woods.

Chesnut is typical of the medium-high Appennines. It is a big tree, quite long living; for centuries it has represented means of nourishment in poor mountain areas. Its workable, hard wearing wood is much used in cask construction.

Cherry

very fine, with a sour-cherry (‘amarena’) flavour. It is an easily worked wood, highly appreciated and beautiful in its pink colouring. Several producers have activated monochromatic batteries made of this essence, as it has been ascertained that Balsamico’s flavour is further enhanced by it.

Vast are the lands devoted to the rearing of cherry trees; in the Vignola area, close to the town of Spilamberto, typical Balsamico area, cherry-trees prosper right at the joining of the flatlands with the first hills of Modena province. Cherry is a medium size tree, seldom passing a 15-metre height; it hates pruning and is therefore reared in the shape it naturally develops in open land. The marvellous sight of its blossoming over vast areas attracts numerous visitors, who come from everywhere to enjoy the unusual, fascinating spectacle.

Acacia

wood is strong, hard and compact and is particularly suited to extra-long lasting utilization, for it ensures near-perfect leakproof performance. The color is straw-yellow, tending toward amber through the years. With regard to the Balsamico it contributes a notable betterment in acidity, thus favoring acetification.

Acacias compose bushes in the vicinities of water courses; they are characterized by the embossed bark. Acacia is a leguminous plant with very heavy, long lasting wood; it easily grows on dykes and in hilly country. The Ark of the Covenant was made of acacia wood.

The Juniper

Delight and Cross of the vinegar maker. There have been many disputes about its use according to the tradition, because if on one hand the unmistakable aroma gives vinegar a strong and immediate characteristic, on the other hand it is not always desirable its “intrusiveness” as there is a tendency to prefer more neutral woods, in order to have a less evident influence on the product. However, it is still one of the most wanted woods in vinegar making, also because of the simple fact it is not easy to find it nowadays, as useful quantities of this evergreen have completely disappeared, at least in the Appennine areas of Emilia Romagna, where in the past centuries it was easily available.

Juniper is an evergreen tree, not very big, spontaneous in many Apennine areas, but lately it is difficult to find because of the small number and the insufficient size of the remaining specimens. Resinous wood and very long lasting, it enjoys a high reputation in vinegar production.

The Ash Tree

Heavy compact with a hard fiber. It is a neutral wood in that it does not transmit any tannin to the balsamic vinegar, being devoid of it. In fact, its white color with an elegant grain also favors acidity without altering the color in any way.

Ash is a tree that has always been an integral part of the ancient wooded areas of the provinces of balsamic vinegar. Tree of vigorous growth can reach remarkable dimensions, its white wood is very used in carpentry and for this reason it is encouraged. In the local iconography is often present as a testimony of its endemic presence, frescoes paintings and pictures of the past as well as in heraldry.

The Mulberry Tree

It was very present in the past being often used in the “piantate”, the rows placed at the limit of the agricultural properties. The choice on this tree was favored by the activity of silkworm breeding which constituted a form of integration of the meager family budget of the farmer. This activity disappeared before the Second World War, but the mulberry tree has remained in the vinegar cellar because its porosity, due to the large spring circles, favors a rapid concentration of balsamic vinegar. Deep yellow as soon as it is cut, it oxidizes quickly acquiring a dark reddish color. Soft and well workable wood.

Mulberry, a medium-sized tree planted intensively in the 1800s due to the spread of the silkworm economy in our area. To round out the meager household budget, the women of the house “went to the leaf”, that is, they procured the leaves of this tree with which they fed the precious larvae in special containers. Porous wood with wide spring circles, the leaves vaguely recalling the vine, are easily attacked by insects and viruses.

The Oak

It has always been considered the tree par excellence. In our area, even the toponymy, an example of which is the town of Rovereto di Modena, shows that there were once extensive forests of this essence. The most frequent varieties are the Farnia, a sort of oak of the wetlands, a majestic tree that can reach 30 meters in height and is very long-lived, the Rovere, called robur for its qualities of resistance, more widespread in the hills, as well as the Roverella which, despite its name, also reaches considerable dimensions.